Zen Kōans

In this post, I talk about practicing with 'kōans' which originate from Zen Buddhism.

Background

Over the last few weeks, my meditation practice has focused on Zen Buddhist kōans, guided by Henry Shukman on the Waking Up App.

According to Merriam Webster, a kōan is “a paradox to be meditated upon” and it “is used to train Zen Buddhist monks to abandon ultimate dependence on reason and to force them into gaining sudden intuitive enlightenment.”

Kōans can take the form of phrases, stories, dialogues, questions, or statements; and, as said, they can trigger a sudden enlightenment experience. We simply sit with a kōan, not trying to understand it conceptually—they are not riddles or puzzles to be figured out through reason. Rather, we must simply sit with the kōan and let it fizzle its way through our experience. Manifesting its deeper meaning on its own accord.

Kōans have been described as “…unsolvable enigmas designed to break your brain.”

While they originate from Zen Buddhism, they can form the basis of an entirely secular meditation practice. No metaphysical beliefs or rituals are required—really, all that is required is experience and an attitude of curiosity and genuine openness.

Examples

Even though the aim is not to understand kōans, some are more intuitive than others. For instance: ‘Beginners Mind’, ‘Ordinary Mind is the Way’, and ‘What is your original face before your parents were born?’

Meanwhile, others are much more esoteric but are equally as powerful once they are teased out. For instance: ‘One Finger’, ‘Seamless Tomb’, ‘Two hands clap and there is a sound. What is the sound of one hand?’

Not Knowing is Most Intimate

But by far my favourite kōan is a story which culminates in: ‘Not Knowing is Most Intimate.’

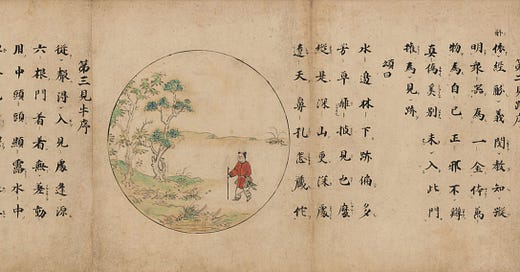

The story is about a young monk, Fayan, on pilgrimage. Instead of having a particular destination, like a holy site or a shrine, he decided to go on a spontaneous journey to visit different monasteries. However, the journey was disrupted by a snow storm, so he lodged at a particular monastery for a few days.

After the storm subsided, Fayan was about to leave; but, a senior monk, Dizang, asked him, “What are you doing?” To which he replied, “I am on pilgrimage, going where the wind takes me.” Dizang then asked, “What is pilgrimage?” Fayan, confused, proceeded to think for a moment or two and replies by saying, “I don’t know.” Dizang then said, “Not Knowing is Most Intimate.” And, Fayan had a deep awakening.

But what exactly does this phrase mean? As said, the aim is not to reason our way through kōans, but rather to feel them experientially. From the point of view of our direct experience, what does it feel like to ‘not know’? What happens if we refrain from labelling objects in our experience? What happens if we let go of all the concepts we have? What happens if we let go of our assumptions of how the world is or should be? What happens if we stop defining our experience?

“All thoughts crave to be believed.” — Adyashanti.

When we refrain from labelling, let go of concepts and assumptions, and stop defining our experience, we are free to directly connect with our experience. To simply experience experience directly—without the obstacles of the conceptual mind. When we admit to not knowing, we let experience be just as it is, and we meet it as it is.

Objectively speaking, there is nothing particularly special about Dizang’s question. But the effect it had in Fayan’s experience was profound. It provoked an awakening from the confines and constraints of his conceptual mind. And, by abiding in the simple, open space of not knowing, Fayan had a deep realisation.

Not knowing is a release of our preconceptions, it is an embrace of humility, it is an embrace of openness. And when we abide in the space of not knowing, we are free to intimately and unconditionally embrace all experience. Not Knowing is Most Intimate.

Experience

Kōans, regardless of the form they take, can trigger an unexplainable openness to experience. An unshakable presence, an awakening to the present moment. A feeling of spaciousness, a sense of expansiveness. A subtle stillness which permeates and invades all experience. Quietness and peace.

In truth, kōans do provoke a deep realisation, an awakening to reality. And, while this may fade (or, rather, while we may overlook this realisation or awakening), we can always return to it throughout the day by simply remembering the relevant phrase.

But, as said, we miss the point if we attempt to ‘solve’ a kōan. In order to have their intended effect, kōans must be understood and felt experientially—and not through our reasoning and analytical mind.

Feel the kōan, and see what happens.